[Click on the images to see larger versions]

In June 2008, on the way to a conference, I had the opportunity to visit the villages where my paternal grandparents, Rose (Schwartz) and Harry Bessen, lived before coming to the US. They came from Śliwnica (shliv-NEETS-ah) and Drohobyczka (dro-ho-BISH-ka), respectively, both a mile or two from the small town of Dubiecko (doo-BYETS-ko). We know this from Ellis Island records, among other sources. Joyce and I met our daughter Lauren and son-in-law Chris Bebenek (in Poland, Krzystof Bębenek) in Warsaw where we visited with Chris's grandparents, then toured Kraków (see photos and more photos). On Saturday morning we took a train to Rzeszów, then rented a car to drive the 50 km to Dubiecko (fortunately Chris speaks Polish, because the Avis office was not where Avis had told us it was...).

In June 2008, on the way to a conference, I had the opportunity to visit the villages where my paternal grandparents, Rose (Schwartz) and Harry Bessen, lived before coming to the US. They came from Śliwnica (shliv-NEETS-ah) and Drohobyczka (dro-ho-BISH-ka), respectively, both a mile or two from the small town of Dubiecko (doo-BYETS-ko). We know this from Ellis Island records, among other sources. Joyce and I met our daughter Lauren and son-in-law Chris Bebenek (in Poland, Krzystof Bębenek) in Warsaw where we visited with Chris's grandparents, then toured Kraków (see photos and more photos). On Saturday morning we took a train to Rzeszów, then rented a car to drive the 50 km to Dubiecko (fortunately Chris speaks Polish, because the Avis office was not where Avis had told us it was...).

I was struck by how beautiful the terrain is. After seeing grainy black-and-white photos of shtetl life, I had imagined things were dreary and covered with mud, lots of mud. Instead, the area reminds me of the hills of West Virginia.

I was struck by how beautiful the terrain is. After seeing grainy black-and-white photos of shtetl life, I had imagined things were dreary and covered with mud, lots of mud. Instead, the area reminds me of the hills of West Virginia.

View of Dubiecko from the San River south of town

And my grandparents lived in two “hollers” north of town, each carved by a small stream that runs south into the San. We first traveled up through Śliwnica.

And my grandparents lived in two “hollers” north of town, each carved by a small stream that runs south into the San. We first traveled up through Śliwnica.

Road through Śliwnica

Rose told a story about fishing in this stream with her sister, Fanny, using wooden baskets to toss the fish onto the bank. One time she saw a snake and was frightened, but brave Fanny caught the snake in the basket and tossed it out of the stream.

Rose told a story about fishing in this stream with her sister, Fanny, using wooden baskets to toss the fish onto the bank. One time she saw a snake and was frightened, but brave Fanny caught the snake in the basket and tossed it out of the stream.

Their grandfather's grist mill was also powered by this stream. We looked for evidence of a mill race or an old mill building. We saw plenty of old buildings, but could not identify a mill. I suspect that the small-scale farming done here became uneconomical for wheat crops long ago and mill buildings were re-used for other purposes.

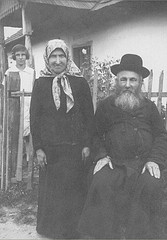

Note the similarity of the building on the left to this one circa 1915 of Rose's grandparents (and Fanny?)

Note the similarity of the building on the left to this one circa 1915 of Rose's grandparents (and Fanny?)

The old school in Śliwnica, now a community center. [Did Rose and her siblings attend this school?]

The old school in Śliwnica, now a community center. [Did Rose and her siblings attend this school?]

Not every building was old. There were plenty of new buildings, many with satellite dishes. The population of Dubiecko is much larger than it was 100 years ago and the area has experienced rapid economic growth over the last 10-15 years.

This is the Śliwnica firehouse.

Likewise, we saw people both in modern dress and in traditional peasant garb. We saw people mowing hay with scythes and people clearing brush with gasoline-powered weed-wackers. Driving cars and driving horse carts...

The town of Dubiecko has 3 east-west streets (including the main highway), intersected by several cross streets.

The school in Dubiecko. [Was this the school Shiya Bessen's children attended in 1939?]

We set out to find the Jewish cemetery. A stork conveniently marks the street on the north side of town.

We set out to find the Jewish cemetery. A stork conveniently marks the street on the north side of town.

This is very likely where my great-grandparents, Shimon and Shaendel (Lustig) Bessen, are buried, as well as my great-great-grandfather, Wolf Schwartz, and, perhaps others.

This is very likely where my great-grandparents, Shimon and Shaendel (Lustig) Bessen, are buried, as well as my great-great-grandfather, Wolf Schwartz, and, perhaps others.

The Nazis removed all the headstones; they paved roads with them. But some large oak trees remain. Judging by the girth of these trees, they likely pre-dated the Nazis by many decades. If the Nazis intended to erase memory of the Jews, they failed. The stark simplicity of the burial ground evokes a much more powerful memory than had the headstones remained.

The Nazis removed all the headstones; they paved roads with them. But some large oak trees remain. Judging by the girth of these trees, they likely pre-dated the Nazis by many decades. If the Nazis intended to erase memory of the Jews, they failed. The stark simplicity of the burial ground evokes a much more powerful memory than had the headstones remained.

The fence around the cemetery is new. A bit of the original wall remains.

The fence around the cemetery is new. A bit of the original wall remains.

We then headed up to Drohobyczka on the western side of town.

This village seems larger, with its own, new school and a Catholic church.

This village seems larger, with its own, new school and a Catholic church.

Also, the valley seemed wider, the farms larger and more prosperous. It was somewhere here that Shimon Bessen ran a tavern. We saw a small, decrepit bar on this road, but did not photograph it. We also had coffee at the tavern on the main street in Dubiecko.

Also, the valley seemed wider, the farms larger and more prosperous. It was somewhere here that Shimon Bessen ran a tavern. We saw a small, decrepit bar on this road, but did not photograph it. We also had coffee at the tavern on the main street in Dubiecko.

Drohobyczka also still has traditional farming.

I was drawn to make this visit by the stories my grandmother told of her childhood. She had such joy, for example, telling us about swinging in her grandfather's cherry trees with Fanny—he had nine trees, each a different variety. In this beautiful and fertile place, I could imagine her life then and the lives of my other ancestors there.

I suppose this is important to me because I want to have some sense of heritage that is not predominately one of victimhood. Yet the joy of this place was not without its tragic consequences. Surely this is part of what drew Shiya Bessen back here from New York.

Shiya and most of the other Jews of Dubiecko survived the original occupation by the Germans in 1939. Most were expelled across the San River into territory controlled by the Soviets (see this historical account of the Jews of Dubiecko). Many went or were sent further east and some survived the war, including Shiya. Tragically, he was killed by a Polish neighbor on his return. (See this book for some insight into Polish violence against Jews after the war.)

Shiya and most of the other Jews of Dubiecko survived the original occupation by the Germans in 1939. Most were expelled across the San River into territory controlled by the Soviets (see this historical account of the Jews of Dubiecko). Many went or were sent further east and some survived the war, including Shiya. Tragically, he was killed by a Polish neighbor on his return. (See this book for some insight into Polish violence against Jews after the war.)

Such thoughts made the visit bittersweet, yet still we made a connection to the lives of ancestors that were very different from our own. And this difference makes me more appreciative of the considerable journey my grandfather began a century ago.

- More photos of our trip by Lauren and Chris and by Joyce and me

- More info on Jews in Dubiecko.

- Bessen genealogy web site. Contact Jim Bessen for a password.